Brian Moskal | Greenberg Glusker

California environmental agencies recently issued a draft vapor

intrusion guidance document that will significantly impact the

investigation and remediation of environmentally impacted

properties by owners, operators and potential buyers.

The guidance document will also impact real estate deals and

development involving those properties.

The California State Water Resources Control Board, San Francisco

Regional Water Quality Control Board and California Department

of Toxic Substances Control released their “Draft Supplemental

Guidance: Screening and Evaluating Vapor Intrusion” for public

comment on Feb. 14.1

The draft guidance attempts to standardize and render consistent

the approach that various California environmental agencies with

overlapping jurisdiction take regarding vapor intrusion.

If promulgated in its current form, this guidance document could

make regulatory compliance for these properties significantly

more difficult, expensive and time-consuming.

Real estate and environmental lawyers, property owners and

developers, and environmental consultants should accordingly

familiarize themselves with the draft guidance. They may also wish

to advise potentially affected clients of the likely implications and

the June 1 public comment deadline.

BACKGROUND REGARDING VAPOR INTRUSION

Vapor intrusion occurs when certain volatile chemicals released to

the ground or subsurface contaminate soil or groundwater. Gases

formed from the volatilization (i.e., evaporation) of these chemicals

can migrate up through soil and into buildings and homes via

basements, crawl spaces, cracks in foundations, sewer lines, gaps

around utility lines and other pathways.

Chemicals that can cause vapor intrusion include trichloroethylene,

also referred to as TCE, and tetrachloroethylene, which is also

known as PCE. These solvents are commonly used by dry

cleaners and as industrial degreasers in manufacturing and metal

degreasing processes.

arious agencies have identified them as carcinogenic or

potentially carcinogenic and harmful to human health in other

ways. Benzene, which is associated with releases of gasoline and

diesel fuel, is also volatile. It has been deemed carcinogenic and

can cause vapor intrusion.

Historically, regulators were primarily concerned with subsurface

chemical impacts to groundwater that might be used as drinking

water or for other purposes. But some of that focus is now shifting

to vapor intrusion as health impacts from subsurface chemical

vapors, and their migration pathways into overlying buildings,

are better understood and testing equipment can measure ever-smaller concentrations.

TCE in particular raises vapor intrusion concerns with regulatory

agencies. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the

Department of Toxic Substances Control have issued guidance

documents indicating that even very low levels of TCE in indoor

air — as low as 2 micrograms per cubic meter for residential uses —

may present an unacceptable risk to sensitive occupants such as

children, pregnant women, sick people and the elderly.

These guidance documents state that these low levels can also

damage developing fetal hearts when pregnant women breathe

the impacted air.

For perspective, 1 microgram per cubic meter is roughly equivalent

to a drop of liquid in five Olympic-sized swimming pools.

Vapor intrusion problems may also be widespread. Properties

contaminated with chemicals that can volatilize into indoor air are

located throughout California and across the nation.

Much of that contamination stems from historical business

operations as varied as electronics manufacturing, metal barrel

refurbishing and dry cleaning.

Some of these operations date back more than a century, when

little was known about the potentially harmful health effects of

exposure to very low levels of these chemicals.

In those early periods, it was common and often legal

to dispose of these chemicals and associated wastes

by discharging them into unlined ponds or even simply

discharging them onto the ground.

Nevertheless, those companies may remain responsible

under environmental laws and sometimes lease provisions

to address their historical impacts to human health and the

environment. In many cases, the properties that are now

posing vapor intrusion risks were thought to be cleaned up.

In fact, some of them have received a clean bill of health

from regulators. These historical impacts affect real estate

transactions when they are discovered by buyers during the

due diligence period.

Addressing potential vapor intrusion issues at potentially

impacted properties can be complicated and expensive. It

generally begins with assessment work. This can entail testing

soil, soil gas and groundwater under and near buildings, and

indoor and ambient outdoor air to assess indoor air chemical

concentrations and to compare those concentrations with

outdoor air to rule out external sources.

Contaminants in soil and groundwater that exceed regulatory

levels may need to be mitigated through measures such as

installation of vapor barriers on foundations, optimization

of heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, or

construction of subslab depressurization systems to vent

vapors to the outdoor air.

Contaminants may also need to be remediated through

elimination of the chemicals in the subsurface to reduce or

eliminate vapor intrusion problems.

DRAFT GUIDANCE PROVISIONS

The draft guidance includes four primary recommendations

for assessing possible vapor intrusion into buildings in

California.

First, it recommends using attenuation factors the EPA

promulgated in 2015.

Attenuation factors are multipliers used to extrapolate

chemical concentrations detected in subsurface soil gas

or groundwater to indoor air concentrations. A consultant

essentially takes the subsurface concentration and multiplies it by the attenuation factor. This calculation yields the

predicted indoor air concentration.

For example, the draft guidance specifies a multiplier of 1

for crawl space chemical concentrations. This means the

guidance assumes 100% of the chemicals in the crawl space

intrude into indoor air — an assumption that some find

unrealistic.

Similarly, the multiplier for groundwater is 0.001, meaning

it is assumed that 0.1% of the chemical in groundwater will

enter into indoor air.

Some practitioners criticize this attenuation factor approach

as overly simplistic. Existing modeling can, in some cases,

use factors such as properties of the chemical at issue, soil

type and porosity, building age and size, and other factors

to develop a more nuanced, site-specific assessment of

indoor air. The draft guidance effectively rules out this kind of

modeling analysis.

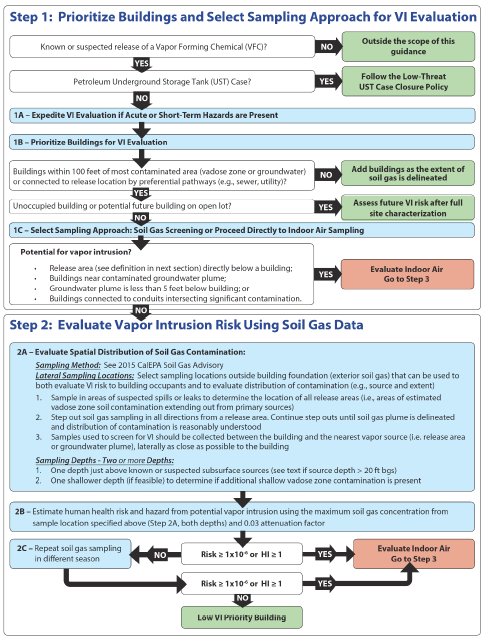

Second, the draft guidance recommends a four-step

evaluation process to determine whether a building located

near a known or suspected source of vapor-forming chemicals

may be affected by vapor intrusion.

These steps are described on the following flowchart and

summarized below.

(1) Prioritize buildings in proximity to the source

contamination. First, determine whether there has been a

known or suspected release of vapor-forming chemicals. If

so, determine whether the release is associated with one or

more underground storage tanks, in which case the property

falls within the State Board’s Underground Storage Tank

Low-Threat Closure Policy and not under the draft guidance.2

If not, the responsible party should evaluate whether acute

or short-term hazards are present based on the type or

concentrations of hazardous substances at issue. Such

hazards may require immediate mitigation or remediation

measures.

According to the draft guidance, buildings within 100 feet of

the most contaminated areas or connected to a contaminated

area by a preferential pathway such as sewer lines, which are

discussed below, should be evaluated for vapor intrusion.

The draft guidance also recommends skipping subsurface

sampling and proceeding directly to indoor air testing

for buildings that meet those criteria plus one of the

following: the release area is directly below the building; a

contaminated groundwater plume is near or less than 5 feet

below the building; or the building is connected to conduits

(such as sewer lines) that intersect significant subsurface

contamination.

If the latter criteria are not met, then the guidance recommends

evaluating vapor intrusion using soil gas sampling instead of

indoor air testing, which is more consistent with the current

regulatory approach and is described in Step 2 below.

(1) Collect exterior subsurface soil gas samples to determine

whether a building may experience vapor intrusion. If, based

on Step 1 above, it is appropriate under the draft guidance

to evaluate possible indoor vapor intrusion using soil gas

data instead of indoor air testing, the next step is to test

subsurface soil vapor chemical concentrations. The guidance

indicates the responsible party should conduct this testing

both near the building in question and laterally from the

suspected source area to determine the nature and extent of

the contaminant impact. The responsible party should also

sample at two or more depths, one depth above the known or

suspected source area and one or more shallower depths to

determine whether additional contamination exists.

Next, the responsible party should calculate human health

risk using the 0.03 attenuation factor discussed above

applied to the maximum subsurface soil gas concentration.

If the calculated cancer risk is greater than one in a million

or the hazard index, which is a measure of non-cancer health

effects, is greater than 1.0, then the responsible party should

conduct indoor air testing.

If the calculated risk does not exceed either number, then the

draft guidance recommends repeating the soil gas testing

in a different season to account for seasonal variations in

subsurface chemical vapor concentrations.

If the calculated risk remains below these numbers in a

different season, then the responsible party can consider it

a low vapor-intrusion priority building and regulatory closure

may be available.

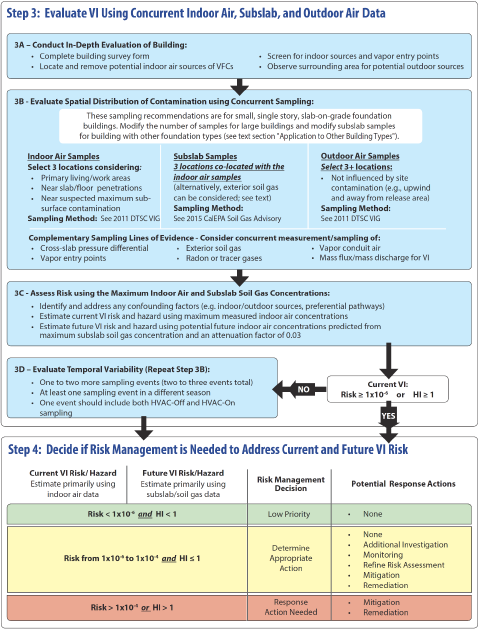

(1) Collect indoor air, subslab gas and outdoor air samples

if a building has vapor intrusion risk. If indoor air testing is

recommended based on Steps 1 or 2, then the responsible

party should survey the building. This includes locating and

removing indoor air sources of vapor-forming chemicals,

which can be more common than one may think, screening

for vapor entry points into the building, and observing the

surrounding area for possible outdoor sources of vapor-forming chemicals.

Under the draft guidance, the responsible party should

select at least three indoor air sampling locations and three

co-located subslab sampling points, which will require

drilling through the floor and building foundation.

These locations should be in primary live/work spaces, near

slab or floor penetrations from which vapors may enter the

building and near the suspected maximum subsurface

contamination.

In addition, the draft guidance recommends selecting three

outdoor locations upwind of the building to determine if any

indoor vapor concentrations may emanate from outdoor

sources rather than vapor intrusion.

The guidance indicates the responsible party should then

estimate vapor intrusion risk using the maximum measured

indoor air concentration and estimate future vapor intrusion

risk using the maximum subslab gas concentration and an

attenuation factor of 0.03, as discussed above.

The draft guidance also recommends conducting this testing

two to three times to account for seasonal variability, similar

to the repeated soil gas testing described in Step 2 above,

and once with the HVAC system on and once off.

(1) Evaluate the need to manage current and future vapor

intrusion risk based on indoor air concentrations and

subsurface soil gas concentrations. If, based on Step 3,

cancer risk is greater than one in a million but less than one

in 10,000, and the calculated hazard index is less than 1.0,

then additional investigation, monitoring, risk assessment,

mitigation and remediation should be considered. If the

cancer risk is greater than one in 10,000 or the hazard index

is higher than 1.0, then mitigation and remediation should be

implemented.

The third core element of the draft guidance is a

recommendation for increased consideration of sewers as a

potential vapor intrusion migration and exposure pathway.

The agencies indicate subsurface vapors can enter sewer

lines that intersect contaminated soil vapor or groundwater

and be transported beneath or directly into buildings.

Given this risk, the agencies recommend sampling indoor

air in a building that meets these criteria even if soil gas and

subslab sampling indicate no significant vapor intrusion risk

because they may ignore the sewer pathway risk.

This could result in more complicated and expensive vapor

intrusion assessments because many buildings have sewer

lines beneath or connected to them that may intersect

contaminated soil or groundwater.

All such buildings may be compelled under the draft

guidance to conduct indoor air sampling that would not be

required under existing guidance.

Finally, the draft guidance lays the groundwork for

development of a California-specific vapor-intrusion database

of information such as vapor intrusion sampling and building

data. The purpose of this database is to understand how

human-caused and natural factors influence vapor intrusion.

The information will be collected via the State Board’s existing

GeoTracker database. A working group within the California

EPA will eventually use the database to determine whether

California-specific attenuation factors are appropriate in

place of, or in addition to, those discussed above.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE DRAFT GUIDANCE

The increased vapor intrusion sampling, mitigation and

remediation requirements set forth in the draft guidance

could increase the cost of vapor intrusion assessments by

as much as 30% to 60%, according to one environmental

consultant.3

One reason is the increased emphasis on multiple lines of

evidence, such as soil gas, subslab, groundwater, and indoor

and outdoor air sampling. In addition, multiple sampling

events over a long period of time to evaluate seasonal

variations will increase the time and cost of assessment and

regulatory closure.

These time frames will be completely unrealistic in many

real estate due diligence contexts, which may result in

creative approaches like environmental escrows, expanded

environmental indemnities and increased use of prophylactic

mitigation measures that may not ultimately be necessary.

Collecting samples from multiple subsurface depths during

each sampling event will also increase complexity and costs.

Finally, the required use of specified attenuation factors in

place of site-specific vapor-intrusion modeling will increase

the number of properties that exceed calculate cancer and

non-cancer risk thresholds.

Due to the coronavirus pandemic, on March 25, the agencies

extended the public comment period until June 1 at noon.

Comments can be submitted to DWQ-vaporintrusion@

waterboards.ca.gov. The agencies have indefinitely

postponed the public meetings previously scheduled for April

regarding the draft guidance.

Property owners and developers, environmental and real

estate lawyers, environmental consultants and other

stakeholders in California should carefully evaluate the draft

guidance and submit public comments if they desire.

Notes

1 DTSC and California Water Resources Control Boards, Public Draft,

Supplemental Guidance: Screening and Evaluating Vapor Intrusion

(February 2020), available at https://bit.ly/34U6DLi (last visited May 4,

2020).

2 State Board, Underground Storage Tank Program, Low-Threat

Underground Storage Tank Closure Policy (last updated Sept. 3, 2019),

available at https://bit.ly/2Kpq3OW (last visited May 4, 2020).

3 Roux Associates, Inc., CA Vapor Intrusion Supplemental Guidance:

Notable Changes and Implications for Developers, Property Owners, and

Responsible Parties (Mar. 5, 2020), available at https://bit.ly/2Vojmml

(last visited May 4, 2020).