Pierre Grosdidier | Haynes and Boone LLP | February 27, 2019

In Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Insurance Company of the State of Pennsylvania, the Texas Supreme Court opined once again on the issue of the extent to which an insurance provision incorporates the terms of an extrinsic contract.[1] The insurance provision in this case was a standard Texas Department of Insurance Form WC 42 03 04 A waiver of subrogation endorsement, but Exxon Mobil’s holding is valid for any insurance provision, including additional insured provisions, that incorporates terms of an extrinsic contract.

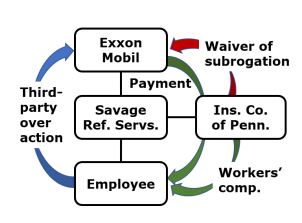

An employee of contractor Savage Refinery Services suffered an injury in an Exxon Mobil refinery (Figure). The employee received benefits from The Insurance Company of the State of Pennsylvania, Savage’s workers’ compensation carrier (“Carrier”) and sued Exxon Mobil in a third-party over action. The employee settled with Exxon Mobil and the latter sued the Carrier to secure a declaration that the Carrier had waived its subrogation rights in a Form WC 42 03 04 A endorsement to Savage’s workers’ compensation policy.[2] Absent a waiver, the Carrier’s subrogation rights grant it a “first money” right to any payment by a third-party (here, Exxon Mobil) to an employee who received benefits from the Carrier.[3] It is not unusual in a construction project that a workers’ compensation carrier waives its subrogation rights in exchange for a policy premium.[4] Personal injury lawsuits allegedly settle more easily and for less in the absence of subrogation rights.[5] And, from the carrier’s perspective, the increased premium buys one less dispute to litigate.

By its terms, the endorsement waived the Carrier’s subrogation rights relative to the party named in the endorsement’s Schedule (the “who”); “‘with respect to bodily injury arising out of the operations described in the Schedule,’” (the “what”); and where the named insured (here, Savage) was “required by a written contract to obtain th[e] waiver” (the “where”).[6] The Schedule did not expressly name Exxon Mobil. The incompleteness of the waiver meant that the Court also had to examine the terms of the parties’ Service Contract.

In their Service Contract, Exxon Mobil and Savage agreed to indemnify each other only for their own negligence, and Savage agreed to waive “‘all rights of subrogation and/or contribution against [Exxon Mobil] . . . to the extent liabilities are assumed by [Savage].’”[7] Therefore, Savage had no obligation to indemnify Exxon Mobil for claims that arose from Exxon Mobil’s tortious conduct. The key question was whether this limitation on Savage’s indemnity obligation conditioned its waiver of subrogation.

The Court held that the scope of the endorsement (like that of any insurance policy) was first determined from its four corners. If the endorsement or policy pointed to an extrinsic document, that document would be referred to only “‘to the extent required by the policy,’” that is, in this case, the endorsement.[8]

Savage’s endorsement specified the “what” (bodily injury) and required a referral to the parties’ Service Contract to determine the “who” and the “where.” The Service Contract defined the “who” as Exxon Mobil, and the “where” as “‘operations [in Texas] where [Savage is] required by a written contract to obtain th[e] waiver from [the Carrier].’” The endorsement did not require any further inquiry and, therefore, imposed no qualifier on 2 whether Exxon Mobil or Savage was ultimately responsible for the injury. For this reason, the Court upheld the validity of the subrogation waiver as to the injured employee’s claim.[9]

The Court contrasted the facts and its analysis in Exxon Mobil with those in, inter alia, Deepwater Horizon. [10] In that case, various BP entities, acting as operator, sought coverage as an additional insured under various insurance policies held by Transocean entities, the drilling contractor. As the Court explained, the insurance policies

at issue in Deepwater Horizon extended “insured” status to “[a]ny person or entity to whom the ‘Insured’ is obliged by oral or written ‘Insured Contract’ … to provide insurance such as afforded by [the] Policy.” The policies defined an “Insured Contract” as “any written or oral contract or agreement entered into by the ‘Insured’ … and pertaining to business under which the ‘Insured’ assumes the tort liability of another party to pay for ‘Bodily Injury’ [or] ‘Property Damage’ … to a ‘Third Party’ or organization.[11]

The crucial difference between the two cases, therefore, was the location of the assumption of liability qualifier. In Exxon Mobil, the qualifier was in the Service Contract, and there was no need to reach it to circumscribe the scope of the subrogation waiver. The consequence was that the Exxon Mobil waiver was valid regardless of which party caused the employee’s injury. Conversely, in Deepwater Horizon, the qualifier was in the insurance policy and had to be factored into the scope of the additional insured provision. In that case, BP was an additional insured with respect to above-surface pollution, for which Transocean had assumed liability, but not with respect to below-surface pollution, for which the driller had not.[12]