Pierre Grosdidier | Haynes and Boone LLP | February 5, 2019

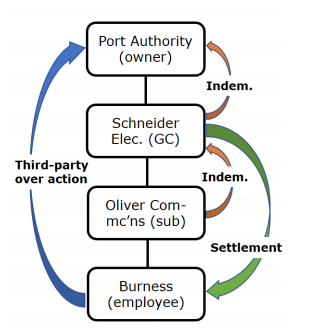

In the usual construction contractual chain, the owner has a contract with a general contractor (“GC”), and likewise the GC with a subcontractor. Indemnity provisions typically ensure that the GC indemnifies the owner, and the subcontractor indemnifies the GC if, for example, an injured subcontractor employee sues the owner in a third-party over action (Figure). At least, that is the way it should have worked—but did not—when a Port Authority, Schneider Electric, and Oliver Communications entered into contracts to install security cameras on a bridge.

Burness, an Oliver employee, sued the Port Authority for an injury sustained on the job site. The Port Authority sought indemnification from Schneider, which eventually agreed to pay a settlement to Burness. Schneider then moved for summary judgment against Oliver for indemnification. The trial court granted the motion and awarded Schneider over $1.2 million against Oliver, but the Amarillo Court of Appeals reversed and denied judgment for Schneider, for two reasons. As a threshold matter, the court reiterated that, under Texas law, “indemnity agreements are strictly construed in favor of the indemnitor.”

The subcontract obligated Oliver to “indemnify, save, and hold harmless” Schneider, its agents and employees, “and all parties indemnified by Contractor in Contractor’s Contract.” In this case, the “Contractor’s Contract” was the contract between the Port Authority and Schneider. Thus, Oliver was allegedly contractually obligated to indemnify Schneider and anyone Schneider was obligated to indemnify. But, after scrutinizing the owner-GC contract, the court determined that Schneider had no obligation to indemnify the Port Authority.

The Contract between the Port Authority and Schneider boiled down to a purchase order that contained no indemnity provision, and that did not incorporate the only document that included an owner-GC indemnity provision (a request for proposal).4 The court held that Schneider, in its motion for summary judgment, failed to prove that it had a duty to indemnify the Port Authority, which meant that Oliver had no duty to indemnify Schneider for Burness’s claim against the Port Authority.5 Schneider, therefore was, not entitled to summary judgment.

The court then turned to the scope of Oliver’s indemnification duty. The subcontractor agreed to indemnify against claims “arising by reason of the death or bodily injury … to the extent caused in whole or in part by any negligent act or omission of Subcontractor [Oliver], [Oliver’s] employees, agents, suppliers, subcontractors or anyone for whose acts subcontractor may be liable and [Oliver] expressly so agrees, whether or not said liability … arises in part from the negligence of Contractor [Schneider] or any party indemnified by [Schneider] in Contractor’s Contract.

Citing to prior Texas appellate cases that have addressed this issue, the court held that this provision required some act of negligence by Oliver or those under it to trigger Oliver’s indemnification obligation. Oliver had no duty to indemnify Schneider and its indemnitees if the latter were “the sole cause of the injury.” But, the court added, the factual record contained insufficient evidence to raise a question of fact regarding the negligence of Burness, Oliver, and those under Oliver. For this additional reason, Schneider was not entitled to summary judgment. There being no basis to Schneider’s summary judgment motion, and inadequate evidence adduced to counter Oliver’s no-evidence motion for summary judgment, the court reversed the trial court and rendered judgment for Oliver.

Counsel’s takeaway from this case is straightforward: check that all indemnity provisions are in place in the construction contractual chain and, when seeking indemnity under a provision such as Schneider and Oliver’s, look for a fact that implicates the indemnitor’s responsibility in the incident and might bar the indemnitor’s noevidence motion for summary judgment.